Chinese Dining Etiquette Survival Guide

A good friend of mine once observed that some people eat to live, and others live to eat. Many Chinese people, myself included, seem to fall into this second category.

For us, our days revolve around food. After breakfast we think about lunch, and after lunch we plan for dinner. In southern China, there are also dedicated times for morning dim sum treats — zăo chá (早茶) ![]() — and guilt-free midnight snacks — yè xiāo (夜宵)

— and guilt-free midnight snacks — yè xiāo (夜宵) ![]() .

.

Food is a central part of Chinese culture. There is great pleasure in sharing meals with family and friends, but there are also important etiquette and table manners, especially in more formal situations.

Chinese formalities around dining are very different, so Westerners who sit down to a delicious meal may sometimes get more than they can chew.

This article walks you through a full Chinese banquet with tips and vocabulary along the way for navigating the dangerous territories of shark fin soup and other dishes.

With this knowledge under your belt, hopefully you can loosen up and enjoy the meal without any worries!

Seating Arrangements

Many restaurants in China offer private dining rooms with large round tables and spinning Lazy Susans.

Seating may not be marked, but don’t be fooled – there are unspoken rules for who sits where.

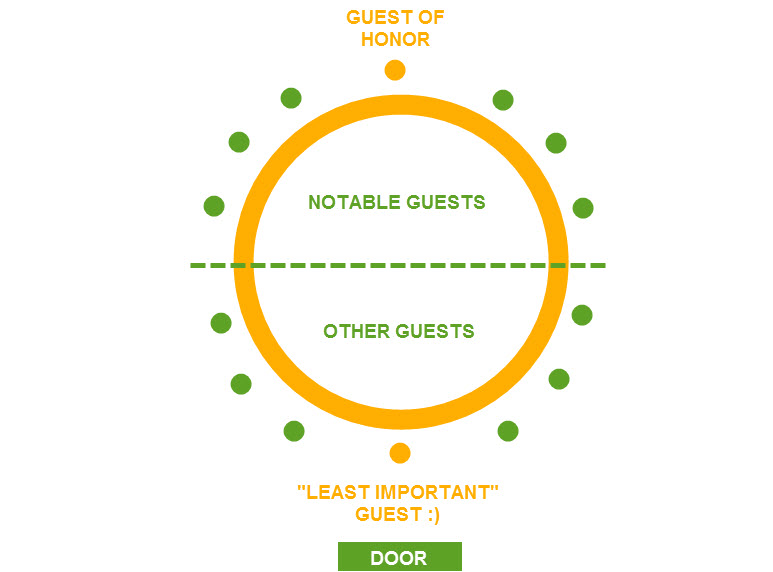

Generally, the "least important" person of a banquet sits closest to the entrance of the room, directing and communicating with servers. The guest of honor sits across, furthest away from the entrance, back facing the wall.

In formal banquets today, being seated far across from the door is a sign of honor. The most notable guests will be seated near the guest of honor position. Other guests sit nearest the door.

Observing the seating arrangement can be a useful way of understanding social relationships and hierarchies. Seating arrangements are less strict at informal gatherings.

The Food

A formal Chinese banquet can involve many courses, with platters of food laid out on the Lazy Susan.

The Lazy Susan eliminates the need to pass the potatoes or ask for yams, but be sure to spin the Lazy Susan in the clockwise direction. If you notice fellow diners sitting with empty plates, it’s also polite to send the platters their way.

Meals typically begin with cold appetizers, such as pickled cucumbers, preserved eggs, cold slices of cooked meat, or sometimes the more exotic pickled jellyfish and duck tongue.

Western food is also gaining popularity in China, so don’t be surprised if you see a Chinese potato salad or Caesar salad.

Soup and small cakes may be served between courses as a palate cleanser, and there are typically many proteins as well as vegetarian dishes.

The main entrée, or zhŭ shí (主食) ![]() , such as rice, is usually the last course, and you might not want to eat too much of it, as it can signify to the host that you didn’t enjoy the rest of the meal. Fresh fruit is often brought out at the end, as a light dessert.

, such as rice, is usually the last course, and you might not want to eat too much of it, as it can signify to the host that you didn’t enjoy the rest of the meal. Fresh fruit is often brought out at the end, as a light dessert.

Fish and seafood are common banquet features, since the character for fish, yú (鱼) ![]() , sounds like the character for abundance, yú (余). Fish is usually steamed whole and laid out so that the head is pointed toward the guest of honor.

, sounds like the character for abundance, yú (余). Fish is usually steamed whole and laid out so that the head is pointed toward the guest of honor.

Note that it is also bad luck to flip the fish after the meat on one side has been consumed, as this is like capsizing a boat and can mean capsizing your fortune. Some diners will even refuse to eat the fish if it has been flipped. The better technique is to wriggle the skeleton of bones loose and pull it away.

When you’re dining in a foreign country, it is not uncommon to encounter food you don’t really enjoy.

Your host may still push certain dishes toward you, or someone may even use their own chopsticks to deliver food onto your plate. They do this to demonstrate their hospitality.

It’s polite to give everything a taste, but if you really must decline, you can cite a doctor’s instruction or a food allergy, shí wù guò mĭn (食物过敏) ![]() . This will prevent you from offending your hosts.

. This will prevent you from offending your hosts.

The Drinks

Tea, juice, and alcohol are some of the most common beverages at a meal, and other guests may often refill your glass.

To keep from disrupting conversation, thank them by simply tapping two or three fingers against the table. This supposedly rose out of a Qin dynasty tradition, when the emperor accepted the three-finger tap as thanks because it represented a prostrate figure. But take note where you make this gesture. This practice is common in Southern China and not necessarily done in other regions.

Alcohol usually flows freely at business meetings or celebrations. bái jiǔ (白酒) ![]() , hard liquor served in small cups, is most common. Beer, wine or other western liquors may also be served. Just keep in mind that they are usually unchilled.

, hard liquor served in small cups, is most common. Beer, wine or other western liquors may also be served. Just keep in mind that they are usually unchilled.

Toasts are common during Chinese banquets, and there may be several versions of the Chinese version of cheers — gān bēi (干杯) ![]() , or "dry cup."

, or "dry cup."

Reaching across a large table to clink cups can feel awkward, so another option is to strike your cup once against the Lazy Susan.

Remember that meals can last a long time, so it’s a good idea to pace yourself with the bái jiǔ (白酒), especially if you are still making that good first impression.

One trick is to keep your lips closed when you raise the cup to your mouth. Although the bái jiŭ (白酒) cups are small, most people take several sips before they actually finish the cup.

At times, personalized toasts may also be raised to the host or the guest of honor. One tradition is to make toasts around the table, so if you ever find yourself in the spotlight, here are a few common toasts to fall back on.

Yoyo Tip: If you'd like to hear the pinyin syllables below enunciated, take a look at Yoyo Chinese's video-based pinyin chart. It has 400+ audio demonstrations for all pinyin syllables and 90+ video explanations for some of the more difficult sounds: /chinese-learning-tools/Mandarin-Chinese-pronunciation-lesson/pinyin-chart-table

For career or personal advancement:

I wish you rise higher with every step!

zhù nĭ bù bù gāo shēng

祝你步步高升 ![]()

For the family man:

I wish your entire family happiness!

zhù nĭ quán jiā xìng fú

祝你全家幸福 ![]()

For the traveler, or for a journey to success (such as for a difficult project):

I wish your path goes with the wind!

zhù nĭ yí lù shùn fēng

祝你一路顺风 ![]()

For general happiness:

I wish you happiness every day!

zhù nĭ tiān tiān kāi xīn

祝你天天开心 ![]()

And, finally, a traditional toast for attaining your heart’s desire:

I wish you good luck!

zhù nĭ jí xiáng rú yì

祝你吉祥如意 ![]()

The Bill

Finally, with bellies full and appetites sated, we arrive at the dreaded bill. In the simple scenario, an obvious host who has planned the banquet will also take care of the bill.

Unfortunately, most situations are more complicated.

Chinese people love to qĭng kè (请客) ![]() — invite guests — whether it’s out to a restaurant or to a dinner party with home-cooked food.

— invite guests — whether it’s out to a restaurant or to a dinner party with home-cooked food.

But even among friends, there may be some mental record-keeping of whose turn it is to qĭng (请) ![]() .The tradition of fighting for the bill stems from fighting to have the honor to host and to invite others.

.The tradition of fighting for the bill stems from fighting to have the honor to host and to invite others.

Nowadays, opinions are split between whether going Dutch, or "AA zhì (AA制)"![]() is acceptable or not.

is acceptable or not.

In fact, in the Yoyo Chinese Intermediate Conversational Course, we interviewed random Chinese people to hear their thoughts on this matter:

The general consensus is that Chinese people still prefer not to split the bill, so here are my tips for handling various nuanced scenarios:

1. Always make an offer to pay the bill. Here's how it's commonly expressed:

我来吧 (wŏ lái ba) ![]() - Let me get it / allow me

- Let me get it / allow me

2. If you are serious about demonstrating etiquette and impressing fellow diners with your manners, then offer to pay once or twice more after your initial offer is rejected. You can say:

不,不, 我来吧 (bù, bù, wŏ lái ba) ![]() - No, no, I’ll get it

- No, no, I’ll get it

or

别,别,别,我来吧 (bié bié bié wǒ lái ba) ![]()

3. If you’ve made your offers and are ready to end the dispute, then you can give yourself an out by saying you’ll get the next meal

行,那下次我请 (xíng, nà xià cì wŏ qĭng) ![]() - Alright, I'll treat next time

- Alright, I'll treat next time

4. If you actually want to get the tab, then you can tell your friend to get you next time:

下次你再请 (xià cì nĭ zài qĭng) ![]() - You can treat next time

- You can treat next time

Remember that sometimes, people will be offended if you actually get the bill, because it suggests that you don’t believe they can afford the bill. Saying that they can pay for the next meal helps keep their pride intact.

Of course, on the other hand, they may have already paid for the previous meal, and are ready for you to get this one, and they only offered to pay because they, too, observe good etiquette.

5. If you are truly adamant about paying the bill and your fellow diners refuse to allow it, then direct their attention elsewhere (perhaps by planting a diversion), and grab the bill the moment they look away.

Make a dash toward the cash register, keeping your elbows out to defend against a counter attack. Be prepared to dodge and wrestle your way forward. After all, a post-dinner skirmish is the perfect way to burn those calories.

Confused about anything? See other kinds of etiquette being observed? Tell me about it or your experiences with formal Chinese dining in the comments below.

DIANA XIN | JANUARY 13, 2015

DIANA XIN | JANUARY 13, 2015

Chinese Is Easier Than You Think

Chinese Is Easier Than You Think What Is Pinyin?

What Is Pinyin? An Introduction to the Tones

An Introduction to the Tones The 1st and 2nd Tones

The 1st and 2nd Tones Numbers 0-10

Numbers 0-10 🐎 2026 Year of the Horse: Meaning, Culture & Chinese Expressions for Learners

🐎 2026 Year of the Horse: Meaning, Culture & Chinese Expressions for Learners Learn Chinese Pronunciation RIGHT with the (FREE!) Yoyo Chinese Interactive Video & Audio Pinyin Chart

Learn Chinese Pronunciation RIGHT with the (FREE!) Yoyo Chinese Interactive Video & Audio Pinyin Chart [LIVE] How to Read a Chinese Menu 101

[LIVE] How to Read a Chinese Menu 101 [LIVE]: How Chinese People Actually Speak

[LIVE]: How Chinese People Actually Speak Did You Know You Can Use Yoyo Chinese Like a Mobile App?

Did You Know You Can Use Yoyo Chinese Like a Mobile App? Why do non-Chinese people feel that Chinese is difficult to learn?

Why do non-Chinese people feel that Chinese is difficult to learn? An Untold Love Story of Me and Yoyo Chinese

An Untold Love Story of Me and Yoyo Chinese  6 Awesome Authentic Chinese Foods You Need to Know About

6 Awesome Authentic Chinese Foods You Need to Know About Frequently Asked Questions About Chinese

Frequently Asked Questions About Chinese  5 Things Chinese Women Love About Western Men

5 Things Chinese Women Love About Western Men Chinese Insults: How to Name-Call Like a Pro (Part 1)

Chinese Insults: How to Name-Call Like a Pro (Part 1) Tone Pairs - The Mandarin Language Hack You've Been Waiting For

Tone Pairs - The Mandarin Language Hack You've Been Waiting For